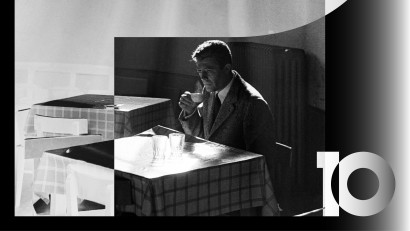

As a filmmaker, Toomas Järvet, says he’s a good listener and a keen observer. Full of curiosity which stayed with him since childhood. Always wanted to see what’s behind that curve in the road, or who’s coming from there. And this might be one of the most essential qualities for a documentary filmmaker, to be interested in the world around you.

Born in Tallinn, Estonia, Järvet has an academic background in law and cultural theory, exploring the intersection between critical thought and the arts. His debut short documentary, “Over and Out” (2012), explored themes of communication, while his first feature-length documentary, “Rough Stage” (2015), is a powerful portrait of a Palestinian theatre director, navigating political, personal and artistic challenges in the West Bank. You’ll be able to meet Toomas at this year’s edition of Bucharest Photofest, so get ready to enjoy his story below.

How did you first discover photography & film

Since I’m already old enough that my childhood went by in the Soviet era, I remember the excitement with which I waited for the weekly new episode of the Polish series Four Tank-Men and a Dog. I wouldn’t go as far as to say that this sparked my interest in photography and film. It’s more connected to high school, when I entered a school with a humanities focus and found myself in a creative, inspiring crowd. I joined a theatre group, and I was captivated by poetry, music, and film. In my last year of high school, I also began to take up photography — my mother gave me her old Zenit camera, and that’s probably when the interest deepened.

Your documentary films

I haven’t really made that many films—altogether three documentaries, plus a few commissioned works for different clients in the advertising world. The first doc was my master’s thesis in visual anthropology at the University of Barcelona — it dealt with the topic of so-called voluntary unemployment. I studied why some people choose to be unemployed voluntarily.

The second one, and at the same time the first, I dare call truly worth watching, was made in Estonia. There, I followed the last shift — and the last firefighter of that last shift — of a small-town rescue squad that budget reductions had cut down. The film that is most important for me personally, and still very relevant, is Rough Stage. It tells the story of Maher, a Palestinian man, who, despite Israeli occupation, Palestinian bureaucracy, a religious environment, and his parents' expectations, pursues his dream of staging a major contemporary dance performance in Ramallah. At a time when, after Hamas’ brutal attack, Israel is trying to demonise, dehumanise, and attack Palestinians as a whole, this film is critical and timely in helping to see beyond media and propaganda. The film demonstrates how dance can convey emotions that words cannot — pain, defiance, and hope.

What is your approach to filmmaking

As a filmmaker, I’m a good listener and a keen observer. And, of course, curious, which, as a child, got me into a lot of trouble and worried my parents and grandparents, since I had a habit of sneaking off on adventures without asking permission. It was always fascinating — what’s behind that curve in the road, or who’s coming from there? I believe that’s one of the most essential qualities for a documentary filmmaker: to be curious about people and the world around you.

What is the role of film in 2025

In the world of fiction film, fascinating things are about to happen. Whether they’re all good, I don’t know — but it’s certainly an intriguing and revolutionary time. With my co-curator and co-director of the Juhan Kuus Documentary Photo Centre, Kristel Laur, we’ve spoken about this: in our field, there is hope. With fake imagery and AI spreading more and more, real stories about real people in the real world become more important than ever. And at this moment, I honestly can’t imagine how AI could replace or attack that.

Your most intense experience as a filmmaker

The most intense experiences are definitely from the filming period in Palestine. To see and live through, over the course of four years, what daily life under Israeli occupation really means… Ironically, you could call it “priceless.” Endless checkpoints, where you never know if you’ll get through, even when you’ve got nothing to hide or fear. Israeli control over natural resources and electricity. Constant restrictions on people’s freedom of movement. Land annexations that continue to this day and are intensifying. The stories you hear and witness… those traumas also stay inside you. That’s what makes it so intense and sharp.

Your main goal when making a film

Even when making a documentary, as an author, you have to be able to create some kind of scenario. You have to imagine what could or might happen in the film. Every author also has their agenda and vision — why and how they want to tell this particular story. That’s also necessary just for applying for funding. But your starting point, where you set off from, might not at all be the same place where you end up. As a filmmaker, you must be aware of the processes unfolding and be prepared to react, adapt, and adjust your course. Sometimes, it even shifts the focus or the goal of the film quite significantly. Because this is real life — and real life doesn’t care about the director’s plans.

Your expectations from Bucharest Photofest

This is our first trip to Romania, and I’m very excited! Actually, I don’t know what to expect — and that’s good. Of course, we’re all influenced by prejudices, but I try to let go of them. Once I had the chance to spend a week together with a Romanian guy, who painted me a very intriguing picture of Romania’s diverse nature and temperament.

I must honestly admit that I don’t know much about Romanian cinema. Two films come to mind right away. The Kafkaesque The Death of Mr. Lazarescu, and the slightly insane Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn, both of which I liked a lot. I also know that you have a powerful school of social cinema.

The experience of curating the exhibition dedicated to Juhan Kuus

For Kristel and me, Juhan’s work is very dear and vital, both because of its content and because of our personal connection with him. About 30 years ago, a completely accidental discovery eventually led to his first exhibition and book in his homeland. Eight years ago, the photo centre we founded together was named after him. I don’t think I’m exaggerating when I say Juhan’s legacy fills a significant gap in Estonian photographic history. Until we brought him into the light for the Estonian photo community, we didn’t have such a highly recognised documentary and press photographer.

Kuus was a documentarian who made visible those stories and people society often ignores: the poor, prisoners, day labourers, the elderly, and other marginalised communities. He also captured historical upheavals with extraordinary intensity, portraying human life honestly and without embellishment, thereby providing us with a cultural and historical memory of great value for future generations.

I believe there’s a real danger that humanity is forgetting what happened in South Africa. Apartheid. Segregation. Dehumanization. We’ve been seeing similar tendencies happening for quite a while already in Palestine and Gaza, where people can be classified as undesirable according to their identity or background, and the open discussion of expelling an entire people from their land is possible. Juhan said of himself: I am the man who goes into the dark, deep forest and comes back to show what life is there, what kind of people you are.

Juhan’s photo stories speak to humanity and dignity, while asking how we take responsibility for one another — a question that never loses its relevance. If only we had more photographers, journalists, and filmmakers like him.

What were the main curatorial challenges

With every Juhan exhibition, the question is always: how can we, within the given limits, provide as broad an overview as possible of Juhan’s 45 years in South Africa? The more we’ve worked with his archive, the less I can say the work gets easier. There’s always the feeling: have we overlooked something, or are we focusing too much on one theme in his work? But I believe that before each exhibition, we’ve made a good selection. Also, we count it as a great success when the audience leaves with curiosity, wondering whether there is something more, something that wasn’t shown in this exhibition, or imagining what else could have been there. That means we managed to spark curiosity and independent thought.

The state of contemporary documentary photography in Estonia

Honestly, this is a somewhat painful topic. May Estonian photographers forgive me, but Estonian documentary photography is in a state of waiting. A kind of paralysis is setting in, as I don’t see new and energetic photographers emerging who want to delve deeply into topics and invest their time and energy in long-term work. I bring you an example. We have some very good ones — today you might call them already classics, like Annika Haas or Birgit Püve — but I ask sincerely, where are the new photographers with strong empathy, with social nerve, with courage, intelligence, artistic quality, and dedication? A single striking snapshot of real life doesn’t make anyone a good documentarian yet. So it’s no surprise that, unfortunately, we don’t see them on the international stage today either. Yes, some do freelance work for foreign press, but that won’t get you to Arles or Visa pour l’Image with a solo show. Meanwhile, in the field of documentary film, Estonia’s situation is positive and exemplary.

Your next projects

On a personal level — although, in truth, it’s also closely connected to our Documentary Photo Centre — I’ve been working on a documentary film about Juhan Kuus for quite a while. And at the photo centre, fascinating times are ahead. This year, for the first time, we received a three-year operational grant from the City of Tallinn, and finally, we can also pay salaries for our work. Together with Kristel, we’re trying to make the most of this period, focusing on ensuring the sustainability of the centre, and of course on creating a strong exhibition and public program. The next exhibition at our centre will present the golden era (1960–1990) masters of all three Baltic states, titled Human Baltic.