Larry Towell began his artistic journey after studying visual arts at York University in Toronto and he is one of the most respected voices in contemporary documentary photography. A member of Magnum Photos since 1988, he has developed a profoundly humanistic body of work over four decades, centered on conflict, memory, land, and the lives of the marginalized. His photography stands out for its poetic depth, political engagement, and unwavering commitment to long-term immersion in the communities he documents.

"The moment that affected me most deeply happened in the 1980s, while photographing in a city dump in El Salvador. A man, about my age, lived there in a cardboard hut with his young daughter. She reminded me of my own child, who was around the same age. He told me how lucky he felt, that he and I were like brothers. I broke down and cried. Couldn’t hold it in", says Larry.

In 2023, he released The Man I Left Behind, a collection of three vinyl LPs featuring original ballads rooted in the people, places, and political struggles he has documented over the years. The project was accompanied by a feature-length documentary of the same name that will be presented in this year’s edition of Bucharest Photofest. Meanwhile, we wanted to find out more about his lifelong career and his vision on today’s world:

How did you discover photography

I took a few pictures when I was young, but I didn’t truly discover photography until I had something meaningful to say — and that happened during the Contra war in Nicaragua. I was interviewing civilian victims of Contra atrocities (the Contras were former National Guardsmen from the overthrown Somoza dictatorship, supported by the CIA, spreading terror in the Nicaraguan countryside).

During those interviews, I took a few simple portraits — not great ones, but a few decent images. Those photographs, born out of that context, were what pulled me deeper into documentary work. They had purpose.

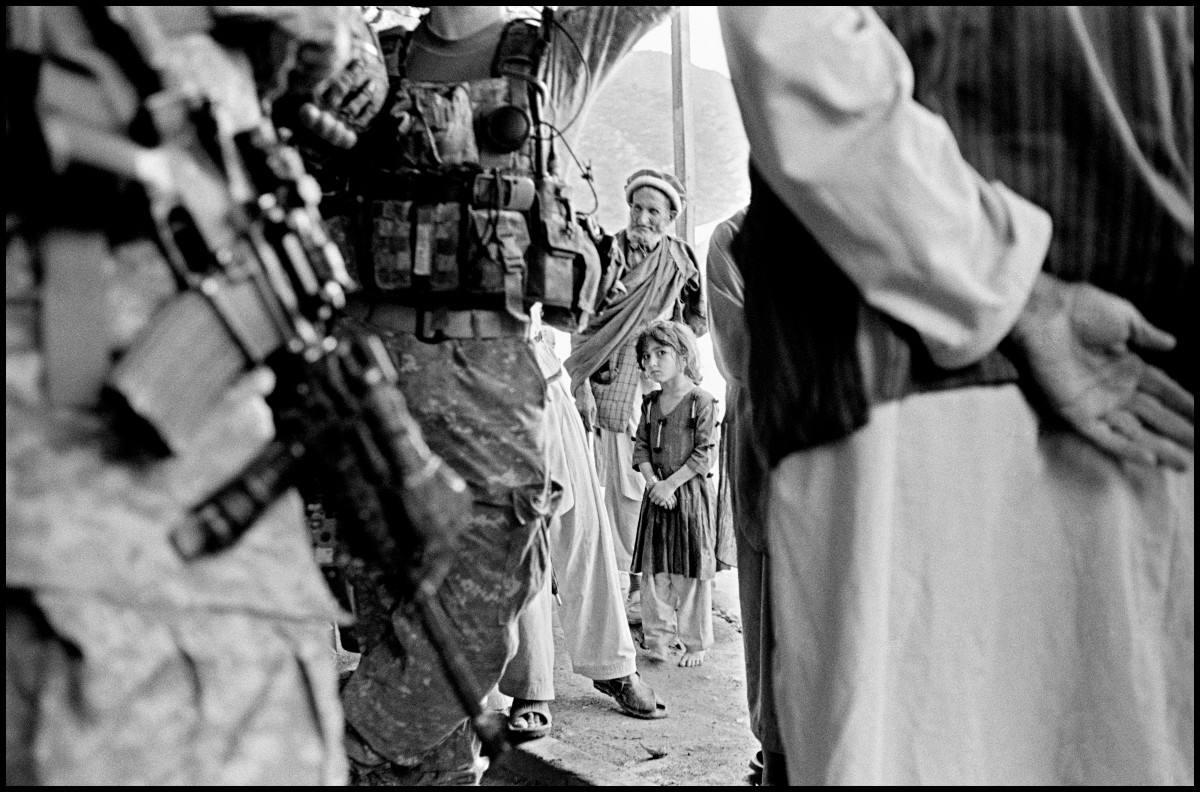

Eventually, I was invited to join Magnum, though their membership process was long and challenging. Photojournalism was alive and strong back then. U.S. foreign policy — alive and sick. Then came El Salvador. Palestine. Afghanistan. Ukraine. Native American issues of landlessness.

At the same time, I also started exploring quieter, peaceful subjects — my own rural family, and Mennonite migrant farm workers near my home. I wanted to be around my kids during the summers. But without that fire in my belly, I’d never have become a photographer. Honestly, I think I owe my career to Ronald Reagan, Vladimir Putin, and Donald Trump.

Your photobooks

My photobooks are about all those people and stories I mentioned — about my interaction with them and their personal histories.

Photography hasn’t really taught me anything, except to stay true to myself and to what I see in front of me.

If you had to pick three photos from your whole career

Probably the most recognized ones — Mennonite Dust Storm, Mennonite Child Asleep on a Cucumber Machine, and the Gaza image from 1993 that won 1st place at World Press Photo. But honestly, those choices were made by others. I don’t really have a favorite.

The most edgy, moving experience

If by “edgy” you mean war stories — I don’t really have any. Most of those are partly manufactured anyway.

The moment that affected me most deeply happened in the 1980s, while photographing in a city dump in El Salvador. A man, about my age, lived there in a cardboard hut with his young daughter. She reminded me of my own child, who was around the same age. He told me how lucky he felt, that he and I were like brothers. I broke down and cried. Couldn’t hold it in.

I’ve documented many war crimes, but that moment hit me hardest.

Has photography lost something essential?

We have everything to lose. The world produces 3.2 billion photos every day — 57,000 every second. Everyone with nothing to say wants followers.

AI has generated more imagery in the past year and a half than all digital photographs ever taken before. Are there even “iconic” images anymore?

No one thought splitting the atom could threaten to destroy the world. No one thought AI could bring Donald Trump.

Expectations from Bucharest Photofest

I wish I could have come to the festival, but I’ve been traveling a lot, and I’m tired — I’m 72 years old. The film helped me reflect on many moments, and I’ve always carried a video camera in my pocket through the years. Hubert Hayaud played a central role in bringing everything together.