Dean C.K. Cox is a journalist, documentary photographer, and media trainer with over three decades of experience in international press, journalism education, and multimedia production. He worked in more than 50 countries across Central and Eastern Europe, Central Asia, the Caucasus, Western Europe, Hong Kong, and the United States. Looks like he lived it all, done it all, from witnessing the 9/11 attacks to hijacked buses and violence on the streets of Kyrgyzstan.

"My very first assignment for the Associated Press in Miami involved the hijacking of a school bus full of autistic children—on my second day on the job. The man on the bus threatened to blow it up. Police eventually stormed the vehicle and shot him dead. I missed the moment—it happened so fast—and that taught me a crucial lesson: be ready at all times", says Dean.

Alongside his academic work, Dean C.K. Cox has built a strong career as a freelance photojournalist and multimedia producer, collaborating with prestigious publications such as The New York Times, The Washington Post, BBC, The Financial Times, Bloomberg News, Geo, Time, Vogue Italia, and Le Monde.

Dean will be present this year at Bucharest Photofest, which will take place between October 10 and 19, with the theme Legacy. Until then, we’re talking with Dean about photography, journalism, and the turbulent times we live in.

How you first discovered photography

My grandfather on my mother’s side and my father were always taking photos during vacations and around the house in 1970’s Germany. This was, of course, during the era of film photography. When I was about 8 or 9 years old, my grandfather gave me a small Kodak cartridge camera that used 110 film. The negatives were tiny and the photos weren’t very sharp, but it was still a lot of fun. I never actually saw the negatives—I'd just drop off the film and a week later receive a stack of prints.

Around the same time, my father was shooting a lot of black-and-white on 35mm film, even making duplicates of old WWI and WWII photos. He would shoot, develop, and enlarge prints in a darkroom, where I sometimes joined him. But it wasn’t until I moved to the US in 1980 that I became more interested in photography. That year I got a Pentax K1000 for Christmas—a classic learner’s camera—and started doing black-and-white street photography just for fun. I think I still have some of those prints in my archive.

As a child, I also read National Geographic regularly. The images of distant places, cultures, and people really fascinated me and left a lasting impression.

The most intense moments as a photojournalist

There are many. My very first assignment for the Associated Press in Miami involved the hijacking of a school bus full of autistic children—on my second day on the job. The man on the bus threatened to blow it up. Police eventually stormed the vehicle and shot him dead. I missed the moment—it happened so fast—and that taught me a crucial lesson: be ready at all times. Key moments often last just a split second.

In Osh, Kyrgyzstan, I was caught up in ethnic clashes between Kyrgyz and Uzbeks. I was punched, kicked, beaten, shot at, and threatened with death. It was one of the few times I had to retreat. Even the police refused to help. It showed me how quickly fear and hate can transform people. Again, the key lesson: be mentally and physically prepared for sudden change.

Another deeply emotional moment was in southern Belarus, documenting a hidden asylum for children with the most severe physical and mental disabilities. I was told it was not a place for the children to live—but to die. The first day was overwhelming—the sights, sounds, and smells were emotionally crushing. I couldn’t even pick up my camera the next day; I just helped the Irish volunteers there. Only after another day did I feel able to photograph again, to show the world what was happening. That experience reminded me: it’s okay to be a journalist with empathy. And that documenting truth is not just a job—it’s a human responsibility.

Were there moments when you just wanted to give up?

I'm not a dedicated conflict photographer, but I’ve been in dangerous situations. In Kyrgyzstan, for example, I had to retreat. But generally, once my journalistic instincts kick in, I become completely focused. Yes, I’ve been detained, threatened, assaulted—by police, regular people, even animals. I’ve had gear destroyed, suffered food poisoning, fallen off buildings, you name it.

But my job is to get the photos. Editors want results, not excuses. I’m always looking for safe positions that still give me strong visuals. And while my safety matters, I also have a duty to deliver.

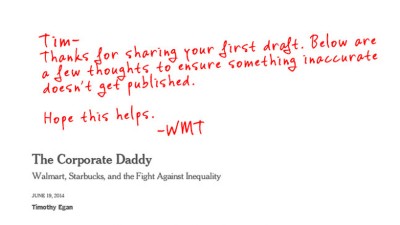

The role of photography in an age dominated by fake news and AI

Images create instant emotional impact. Iconic photos remind us of events, conflicts, and human resilience. A single image can make us cry, laugh, or take action. Unlike video, photos let us linger—pause—and reflect.

Of course, AI, manipulated images, and other technologies are making it harder for audiences to trust what they see. But there are efforts underway—like the Content Authenticity Initiative—that aim to rebuild that trust. We still need truth in images, perhaps now more than ever.

Covering the 9/11 attacks

I was in the CBS News newsroom when the first plane hit. I actually heard it pass over our building before striking the North Tower. I started reporting immediately. When the second plane hit, I realized this wasn’t an accident—it was war or terrorism.

For two days I didn’t have access to my camera (I lived in Brooklyn and Manhattan was shut down), so I coordinated multimedia coverage. When I finally got into the site, the devastation was unimaginable. The smells stuck to my skin and clothes. I learned a close friend had died in the attack—he wasn’t even supposed to be at work that day.

The focus shifted from destruction to recovery. The whole experience was numbing, but we had a job to do.

How important is formal education in photography?

You can learn to use a camera on your own—by making mistakes. But what you do with the camera may require education or mentorship. If you want to be an art photographer, knowing art history and business is useful. If you want to do journalism, I’d recommend at least a degree in journalism. Portrait work? An internship with a pro helps.

A camera is a tool. Knowing how to use it is just the beginning.

How do you see the state of the world?

Society is becoming more polarized. People now seek news that confirms their beliefs. And sadly, many turn away from fact-based journalism toward opinions. Social media has amplified this.

But there are still trustworthy news sources—large and small—doing great work. We just need to look beyond traditional media: think podcasts, Substack newsletters, independent journalists. Information is out there. Finding it takes effort.

Of all the countries you visited, which one impacted you the most?

North Korea. As a journalist, it’s almost impossible to work freely there. Every step is monitored. You don’t know if anything is real. It’s visually fascinating—but journalistically frustrating.

I went there with students and secretly coordinated with a photo agency. They asked for images of military, construction, daily life—but our guides forbade us from taking those very photos. It became a game of stealth. Sometimes I succeeded, sometimes not. Surprisingly, they never checked my camera. Maybe they trusted me, or silently resisted their own system. I’ll never know.

I’d love to return for a longer documentary project.

The experience in Romania

I’ve always enjoyed Romania. My first visit was in 1999 for the solar eclipse. Since then, I’ve returned many times—for work and personal travel. Bucharest is fascinating, and so are the regions beyond the Carpathians. The history, culture, people, food—there’s so much to love. I always look forward to coming back.