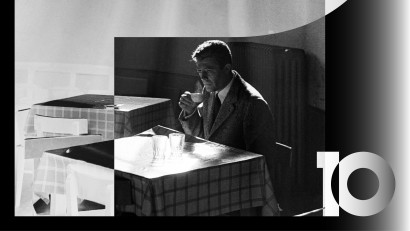

Photographer Tim Smith told us that he can’t wait to meet the people at the tenth edition of Bucharest Photofest in October, especially since there is a historical connection, he says, between the Hutterite communities he documented and Romania. He spent 17 years documenting these colonies in America and Canada, and his project represents the most complex work on this subject.

"Today, documentary photography is more extensive than ever. Talented photographers combine the image with film, sound, text or digital tools to expand the medium. I admire this enormously, because for me, even mastering a single tool to perfection is a challenge", says Tim.

Tim is also a passionate speaker on topics such as slow journalism, photographing sensitive communities or the mental health of journalists. He always takes his skateboard with him, so if you see a guy over 45 taking photos while skateboarding around Bucharest, like he did with young skaters in Iraq, be sure it's Tim. His story below.

The discovery of photography

I grew up in a home where film cameras were always around, nothing fancy—my parents had a Canonet G-III, and my dad showed me a few basics. At the time, I was skateboarding a lot, and photography quickly became a way of holding on to those fleeting moments with friends, of freezing the energy and freedom we felt. I loved the anticipation of waiting for film to be developed, and the ritual of arranging the prints into albums. By the time I was a teenager, I had stacks of albums filled with my early experiments.

When I was 19, my friend Adam brought me a Pentax MZ-50 from China. It was my first SLR, and it opened a whole new world: different lenses, new possibilities. Still, I had no idea what I was doing, nor did I imagine photography could ever become a career. After high school, I drifted—training as a paramedic, trying out university, planting trees for summers. It was during that time that a friend mentioned he was going to study journalism and photojournalism. That was the first moment it clicked for me—people actually make a life out of telling stories with images.

At university, I approached the student newspaper, The Manitoban, simply because I wanted to get into a concert I liked. That led to my first interview, my first published story. For two years, I kept submitting articles and photographs until, eventually, I decided to follow my friend’s path and apply to journalism school. That was back in 2002–2003. From then on, photojournalism became my life.

The documentary photography today

I can’t pretend to speak for the entire field, but I do see an extraordinary amount of powerful storytelling happening. What worries me is the lack of industry support—there’s almost no financial backing for long-term projects, and even short-term visual storytelling rarely receives the investment it deserves. And yet, storytellers keep going. That perseverance inspires me.

Today, documentary work has become broader than ever. Talented photographers are blending photography with film, audio, text, and digital tools in ways that expand the medium. I admire that deeply, because for me even mastering one tool at a time feels like a challenge.

How important is the story behind a photo

The story is everything, but only if it actually comes through in the photograph. The struggle behind making an image may be interesting to talk about later, but it doesn’t matter if it doesn’t show up in the frame. What matters is the story the photograph itself is telling.

Of course, I care about feel and look as well—light, composition, atmosphere. But usually, I begin with a story I want to tell and only then work through the technicalities of how to shape it visually. For me, it often takes many failures, many attempts, before all the elements finally come together in a single image that feels alive. I love photographs that leave me with questions, that refuse to give everything away.

17 years documenting life on the prairies

Seventeen years with the Hutterites has changed me. What I’ve learned above all is the value of connection and community. Their colonies aren’t perfect, but I admire the way life is structured around togetherness—working, celebrating, grieving, simply being present with one another.

Outside their world, society is fragmenting. Loneliness is everywhere, and it’s feeding some of the darker currents in our time. Within Hutterite communities, loneliness is rare. People are woven into each other’s lives. My beliefs and values often differ from those I photograph, yet we can sit down, laugh, argue, share a coffee, and respect one another. We need more of that—more encounters with those who don’t mirror us. Journalism constantly gives me that gift.

Working in the colonies has been challenging and sometimes frustrating, but also the most rewarding experience of my career. Every visit feels as fresh as the first time I set foot in Deerboine Colony back in 2009.

The main challenges in doing your project with insular Anabaptists

Time. More than anything, it takes time to build trust and relationships. Not every community wants to be photographed. Many are protective, wary of how they might be portrayed. Hearing “no” again and again was part of the process, and I had to learn not to take rejection personally.

This project has been self-driven and mostly self-funded, which meant fitting it into an already full life: working at the Brandon Sun as a staff photojournalist, freelancing, applying for grants, preparing exhibitions, writing proposals. There was no roadmap, no ideal equipment, no clear outcome in sight. All I knew was that I wanted to return, again and again, to these communities.

What is your take on slow journalism

Slow journalism, for me, wasn’t a concept I chased—it was born of necessity. Building trust in communities, expanding the scope of the project, balancing it with daily life—suddenly years had passed, and the work had gained a depth only time can bring. I’ve documented children becoming adults, families forming, graduations, weddings, funerals, even shifts in style and technology within the colonies. That’s the gift of time.

Slow journalism is about resisting the rush—to publish, to produce, to “finish.” It means listening, sitting quietly, sometimes putting down the camera. It eases the pressure on both me and the people I photograph.

As for mental health, the truth is complicated. The state of journalism—the constant financial and emotional strain—has taken its toll on me and nearly every colleague I know. The industry is exhausting. But the act of photography itself, of meeting people, of being welcomed into their lives, has been healing. It gives me perspective and connection. The balance, though, comes from remembering to live my own story as much as I tell others’.

From all the countries you visited, which one impacted you the most as a photographer

In truth, no place has shaped me more than my own country. The Canadian prairies, rural life—that landscape has been the foundation of my career, and it still captivates me. The fact that these quiet, understated stories resonate with audiences across the world humbles me.

But travel has also opened unexpected doors. Earlier this year, I went to Iraq to skateboard and photograph the local skateboarding community in Baghdad. I always bring my skateboard with me, wherever I travel for exhibitions or festivals. To be skating with teenagers in Baghdad at 46 years old, trying to keep up with them in the streets—that was unforgettable. The kindness and generosity of everyone I met there was overwhelming. I can’t wait to return.

What are your expectations from the Romanian experience

More than anything, I hope to be surprised. I’m looking forward to meeting people at the festival, celebrating its 10th anniversary, and exploring Romania with my partner.

There’s also a historical connection that makes this trip special: the Hutterites once lived in Transylvania and Wallachia. Discovering more about their past here feels like closing a circle.

Bucharest looks beautiful, and I can’t wait to wander its streets, skateboard in its parks, and enjoy the food and culture. I’m grateful for the chance to take part in this celebration and to experience Romania for myself.